The Confessions

A project by Scott Lawrie Gallery

The Confessions is Scott Lawrie Gallery's first public project. It was held at Silo6 in Auckland, New Zealand from 10-23 July 2022 as a free event for all ages.

The exhibition was inspired by the infamous Scottish witch hunts of the 16th and 17th centuries – desperately cruel, barbaric spectacles of mass hysteria and misogyny – where thousands of innocent women were cruelly strangled and then burnt at the stake.

Witch hunts usually took place at times of political and social upheaval, not dissimilar to those we are witnessing around the world today. The rise of cancel culture, the hysteria of the virtue signallers, the shrill accusations, and the frightening delusions of the religious right have shifted from fringe theories and eccentric beliefs to mainstream narratives in the new culture wars.

The artists invited by curator Scott Lawrie to explore this phenomenon were Patricia Piccinini, Inga Fillary, Amadeo Grosman, Rebecca Hazard, Monique Lacey and Rebecca Wallis. The project was entirely self-funded, except for the generous support of the venue, provided by Eke Panuku Development, Auckland.

All photography © Sam Hartnett.

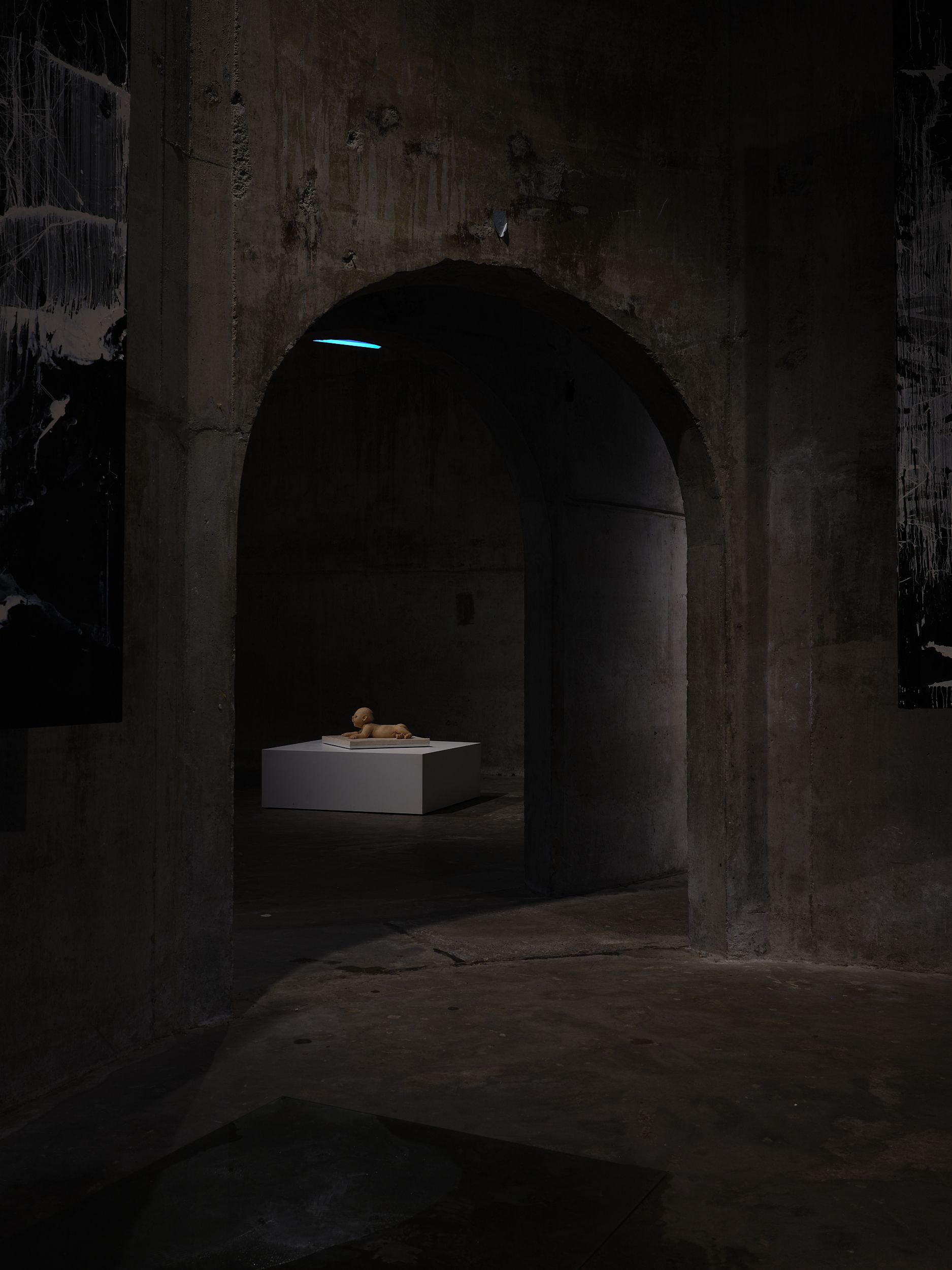

Silo6 is the site of an old cement silo, with six tubular columns, each 35 metres high. The artists were asked to respond not only to the premise of the show, but to the extraordinary space.

It's a perfect setting – a windswept, cold, 'industrial cathedral' on Auckland's waterfront – to play host to a project that is both unsettling, raw, and dangerously candid.

While unashamedly confronting, The Confessions demonstrated how the failures of familiar meta-narratives such as politics, capitalism, and religion have ultimately led us to a dangerous place.

Brand ID by Moffitt.Moffitt

Brand ID by Moffitt.Moffitt

Inga Fillary

Inga Fillary

Rebecca Wallis / Rebecca Hazard

Rebecca Wallis / Rebecca Hazard

Inga Fillary / Monique Lacey

Inga Fillary / Monique Lacey

Rebecca Wallis

Rebecca Hazard

'Though Scotland’s witch hunts occurred centuries in the past, discerning comparisons can nevertheless be drawn with modern socio-political mentalities.'

THE CONFESSIONS

An essay by Tamar Torrance

In a remote village east of the River Nairn, in the Scottish Highlands, Isobel Gowdie was imprisoned and tried for witchcraft. While records detailing the outcome of her trial no longer exist, Isobel’s confessions, divulged over six weeks spent in solitary confinement, were well preserved. Perhaps the most notorious to emerge from a century worth of trials, they read as fantastically elaborate tales of diabolism and black magic, a blend of folklore and ritual, fable, tradition and trauma. Her confessions recount in salacious detail nights spent consorting with the Devil and feasting in the Faery Otherworld, of riding horseback across pitch skies and dancing with the fey, of animal transformations, demonic pacts, murders, and break-ins, alongside her coven of thirteen. Though never confirmed, it is believed that following her trial Isobel was carted to Gallowhill on the outskirts of Nairn, strangled, and burned.

‘The Confessions’ is inspired by Gowdie’s plight, a tribute to those persecuted in the wake of post-reformation hysteria that draws parallels with modern day witch hunts spurred by tribalism, cancel culture, and censorship. Accompanied by James MacMillan’s requiem The Confessions of Isobel Gowdie, this exhibition invites visitors on an immersivejourney through the Silo 6 passages, taking in displays by a range of primarily women artists. Macmillan’s score sets the tone for this experience, his symphony a blend of feverish discord and melancholic spirituality.

The lament begins with a sonorous thrum and visitors are welcomed into the Silo by Inga Fillary’s towering installation Relic. Resemblant of medieval Scottish furniture, the charred paraphernalia surges toward a precarious apex, mimicking the tradition of execution for women accused of witchcraft: burning at the stake. As though buckling beneath an immense heat, the furnishings have fractured in places, their wood splintered and surfaces tarnished by oxidation. Strewn across one of the benches is a medley of instruments; the ominous remnants of torture devices and relics of long-dead Covenanters.

Though explicit in its parallels with Gowdie’s persecution, Fillary’s installation wades ever further into the mire of human history, traversing mourning, grief, denial in a bid to shed light on corruption that persist today. The artist describes the work as a confluence of old and new that exposes the cyclic nature of social control: “Feudalism meets Capitalism”, she writes. Gowdie’s confessions immortalise not only the affliction of an individual, but that of subordinate classes throughout history, where only in death can the burdens of a coercive, exploitative system be disencumbered. For Fillary, death protests the smooth infinitude of Capitalism, embodying an ‘anti-capitalist consciousness’ that ruptures its stultifying embrace with impurity and negation. Caressing the threshold of abjection, Relic materialises that which is most dismaying to being: mortality, and in doing so, disrupts the collective docility with which authority has been subserved from past to present.

A similar note of dissent follows through into the first of Silo’s concrete chambers housing works by Rebecca Wallis. Stripped-back, exposed, and debased, Wallis’ paintings occupy a tenuous space between artistic formalism and somatic viscerality. Though undoubtedly belonging to the realm of abstraction, the surfaces scraped raw and stained in uneven gestures nevertheless appear denotative, bearing an imprint of the artist’s physical encounters with the canvas. Through an act of mimesis, the bisecting, folding, tearing, and pulling-apart of paint raises the viewer’s own bodily awareness, as we imagine swathes of hardened pigment assaulting the silk canvas, which has become unfixed in places and torn away entirely in others. It is difficult not to envisage violent assaults on the recalcitrant female body. Wallis invites viewers to occupy the perspective of both the assailant and the assailed in this encounter, oscillating our attention between the passive surface and the agency of the paint.

In Wallis’ paintings, abjection emerges from the collapse of ‘self’, drawing viewers into a liminal space between states of being, an experience inherently disruptive to our sense of identity and propriety. Rendered unfixed and undefined, ‘self’ seeps into the domain of ‘other’ thought reserved for deviants and transgressors. In this moment, we are ‘other’; and like Isobel and the thousands of women who came before and after her, vulnerable to being ‘othered’.

In the adjoining chamber, Rebecca Hazard’s paintings too recall the soma, her colossal renderings of raw meat an inescapable reminder of one’s own corporeality and the ephemerality of the flesh. Enveloping viewers in tissue, muscle, and fat, the meticulously detailed oil paintings elevate meat from the status of comestible to high-art, their massive scale lending a weightiness to the viscera. While distinctly beautiful, the mesmerising vividness and carefully rendered chiaroscuro possessing a near Baroque intensity, the attractiveness of Hazard’s meat belies its morbidity. Engulfed by Hazard’s raw meat, we become aware of our own bodies as they exist in a state of duality; at once growing and decaying, living and dying. Hazard foregrounds flesh as a gesture toward the transience that presupposes the human condition, to which we are all, without exception, susceptible.

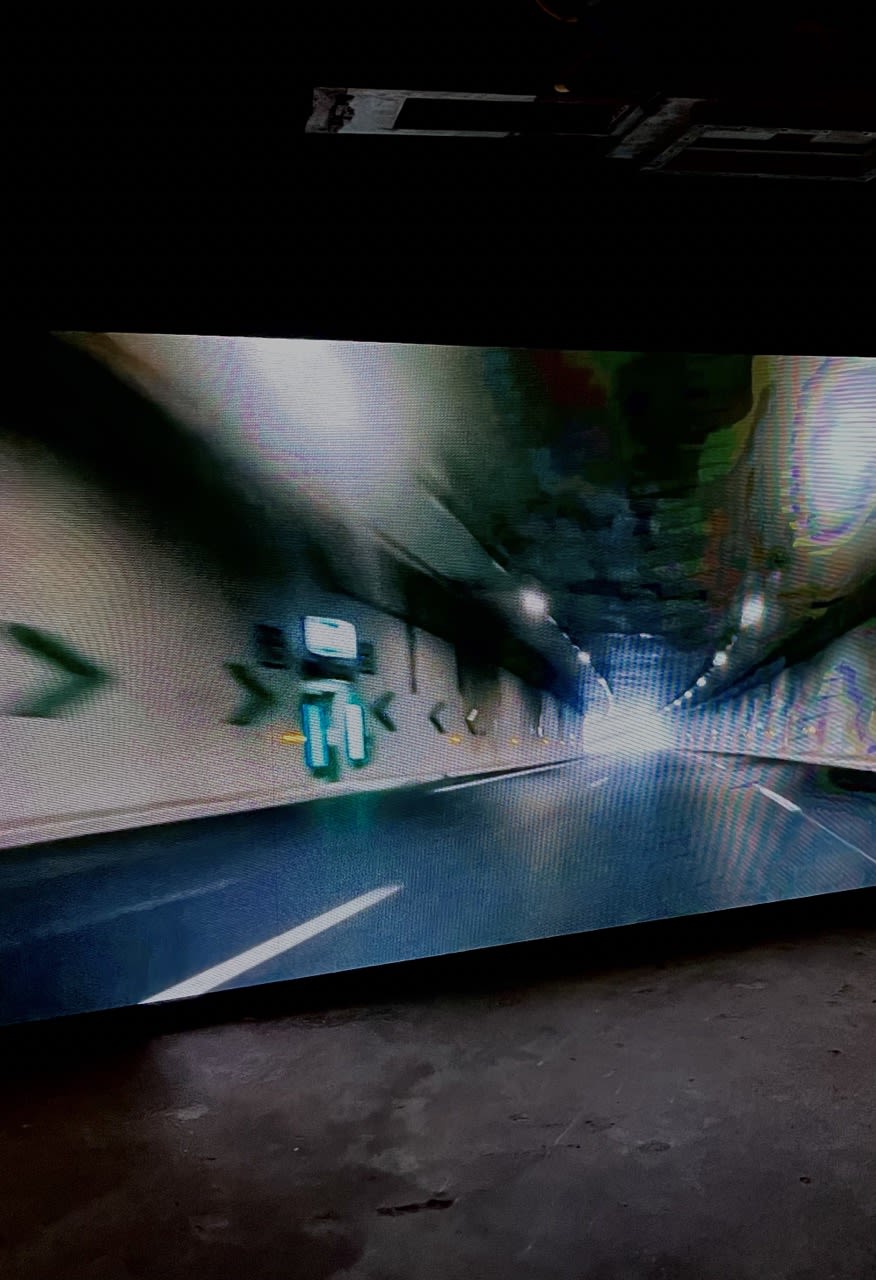

Macmillan’s symphony continues its glissando between fever pitch and mournful resonance, leading viewers into the concrete silo where Amadeo Grosman’s film installation A Tall White Fountain Played resides. Projected across LED matrix screens, the film resembles a stream of consciousness, one which begins with dream-like ambiguity before dissolving into a schizophrenic deluge of imagery. Wrapping a portion of the silo interior, the screens immerse viewers in an accumulation of media, plucked from film, television, the internet and social media, and interspliced with snippets of text that carry the film forward at a jarring cadence. While Grosman’s soliloquy bears a confessional quality - delivered in first-person and without pretence - its chaotic presentation renders any individual voice distorted and impossible to pin down; a metaphor for the warped mirror through which we see ourselves reflected in media.

Grosman describes the work as Koyaanisqatsi for the internet, a reference to the 1980s American non-narrative film and its apocalyptic portrayal of Neoliberalism. Where Koyaanisqatsi is a commentary on the ruinous impact of Urbanism and technology, however, Grosman’s film instead explores the harmful potential of the internet, an aggregate in which toxic culture is unmitigated by time and space. Media is the unrestricted conduit through which ‘capitalist realism’ has become our reality, rendering viable alternatives - political or economic - unfathomable. Despite his cynicism, however, Grosman’s film serves also as a love-letter to the internet, one that relishes in the promise of validation, connection and creativity online, while wrestling with the awareness that such desires are manufactured. Though nevertheless, hope endures, a vestige of the collective desire to overcome boundaries that refuses to abade. Grosman’s film offers a space for redemption should we embrace this desire.

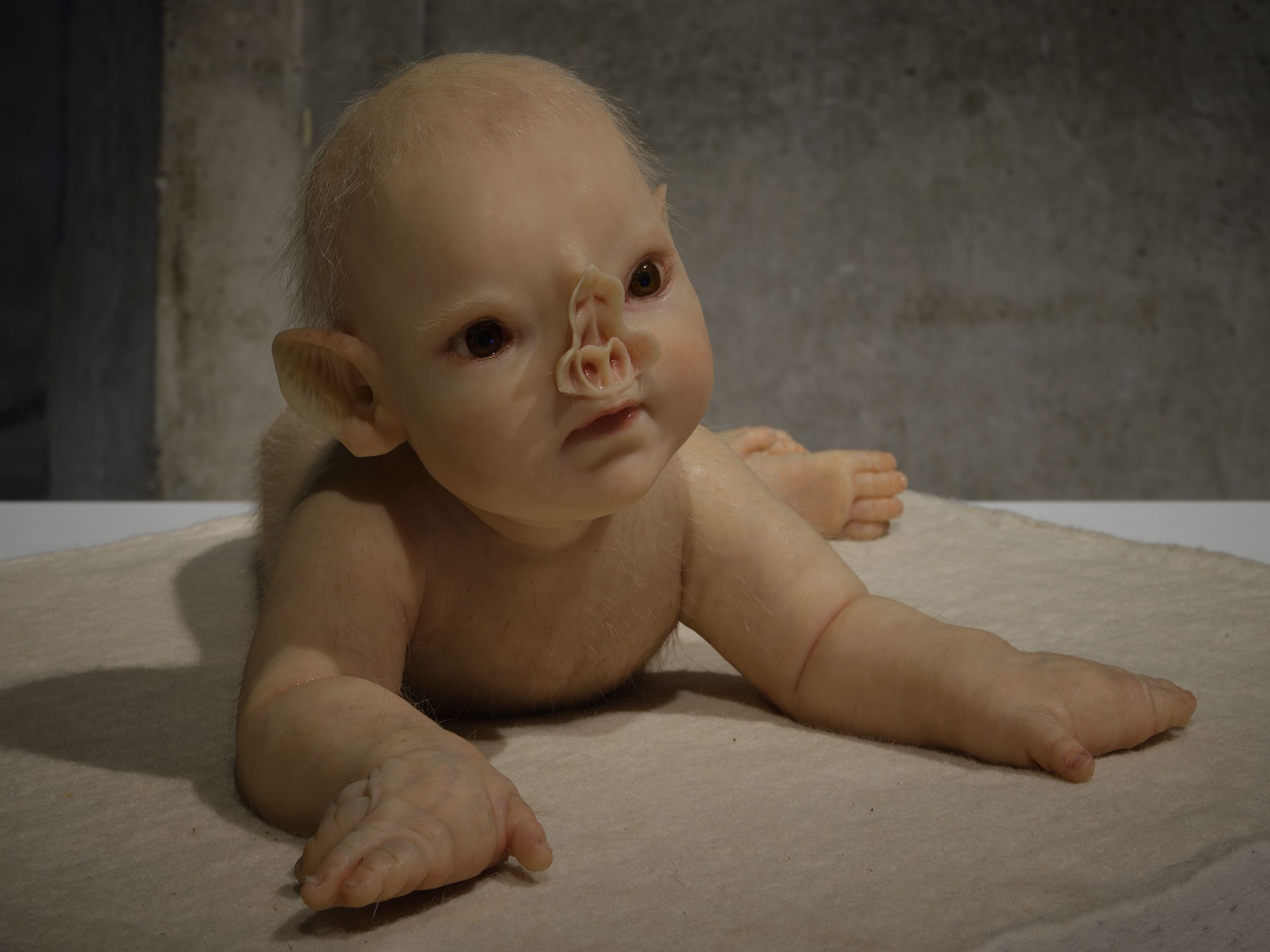

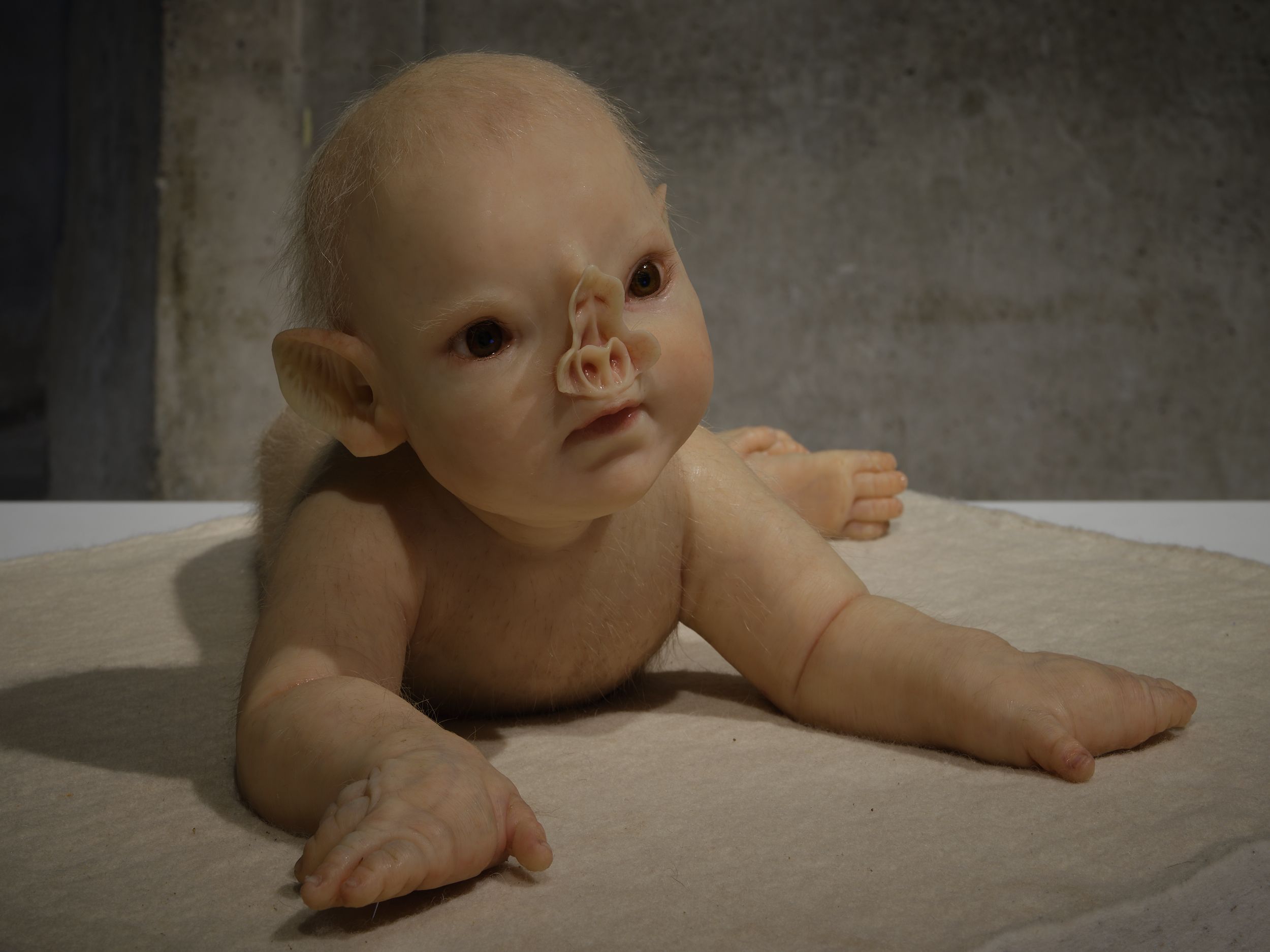

It is this message that carries viewers into the adjoining chamber, where they are met with the impossible hybrid of Patricia Piccinini’s Prone. Rendered in silicone, the baby chimera takes on an uncanny realism; its soft hair, skin and posture undeniably of human origin - or at least, human-adjacent - though nonetheless alien in appearance. Conflating reality with artificiality, normality with aberration, Piccinini’s crossbreed exists in a state of flux, not quite human, but not quite animal either.

On instinct, the sheer strangeness of this creature is something we recoil from; an impulse that is complicated, however, by Piccinini’s tenderness for her subject. At the centre of the room, the infant creature appears unconcerned by our presence, it’s strange beseeching eyes, prone form, and vulnerability triggering an empathetic instinct that is difficult to disregard. Despite perceived differences, it is our similarities to the hybrid creature that resonate. Piccinini encourages audiences to foster this instinct and forgo distinctions between ‘us’ and ‘them’, ‘self’ and ‘other’; a message that stands in opposition to the witch hunt impulse still very much alive in our culture.

In the final chamber, viewers encounter minimalist sculptures by Monique Lacey. In a past life, the matter comprising these works served as ballast bags, receptacles used for stabilisation on boats. In Lacey’s hands, however, the commercial materials are given new form and meaning; their shape transfigured and surface covered in methodic layers of resin, plaster, varnish, paint and pigment. Though having undergone this process of alteration, Lacey describes the sculptures as nevertheless retaining their objecthood, remaining somewhat tethered to the lived world and never entirely shucking prior associations. In this way, her sculptures navigate the permeable membrane between the known and unknown, material and immaterial, revealing the duplicitousness inherent to art and creation. As artefacts of artifice, their true nature is at once revealed and concealed; certainly an apt allegory, Lacey points out, for contemporary politics and social discourse.

Though the message accompanying these sculptures is not one of cynicism, but simply a reminder that not all is as it seems. Lacey’s sculptures are recast following a process in which they are beaten and crushed, taking shape anew in an act of sublimation. While the slumped forms may recall slumbering, or perhaps fallen bodies, Lacey chooses to paint them a brilliant gold; a colour which has captivated artists for aeons, and is treasured universally. Transforming base materials into something meaningful and beautiful, her sculptures speak to the possibility of redemption, and the hope that comes from reconciling with pain.

In the way a melody calls for resolution, so too does our journey through ‘The Confessions’. Macmillan’s score ceases with a mournful sigh, ceding audiences a quiet moment of introspection and reflection. Though Scotland’s witch hunts occurred centuries in the past, discerning comparisons can nevertheless be drawn with modern socio-political mentalities. In the wake of mass upheaval, attitudes born from fear of the unknown and mistrust of the unfamiliar - the ‘other’ and ‘otherness’ - seem only to intensify, exacerbated by hysteria and paranoia. However, these mentalities govern our relationships; and while this may, on the one hand, inspire esprit de corps among your ‘own’, on the other, it translates to a corresponding distinction to and alienation from those who fall outside of your designated ‘side’.

A cursory glance through history reveals how misguided and ruinous such divisiveness can be. It was the same segregation of ‘self’ from ‘other’, ‘us’ from ‘them’, after all, that justified Isobel’s trial and likely necessitated her execution. Traversing the concrete chambers of Silo 6, the consequences of tribalism are laid bare; and yet, we find our way through by way of empathy and compassion. In the silence, reflection bears understanding, resolution and, perhaps, redemption.

Amadeo Grosman

Amadeo Grosman

Patricia Piccinini

Patricia Piccinini

Inga Fillary

Inga Fillary

Monique Lacey

Monique Lacey

Patricia Piccinini / Monique Lacey

Patricia Piccinini / Monique Lacey

Patricia Piccinini

Monique Lacey

I shall go into a hare,

With sorrow and sych and meickle care;

And I shall go in the Devil's name,

Ay while I come home again.

- the spell used by Isobel Gowdie to allegedly transform into a hare.

A MADNESS THAT NEVER GOES AWAY

An essay by Andrew Paul Wood

The trial of Isobel Gowdie in 1662 was one of the last of the Scottish witch hunts. She was a peasant farmer’s wife from Auldearn near Nairn in the Highlands. Her confession of sabbats and spells were delivered without torture, and are remarkable for their lurid detail, seemingly patched together from folklore, the old fairy faith, PTSD (Auldearn was the site of one of the battles of the War of the Three Kingdoms in 1645) and perhaps hallucinations from a bout of ergot poisoning.

Gowdie was very likely executed but the records no longer survive, and the events inspired the 1990 symphonic work The Confession of Isobel Gowdie by Scottish composer James MacMillan as a kind of requiem for Gowdie. This piece of music is the audio accompaniment to The Confession and sets its tone. When it premiered at the UK Proms that year, broadcast live by the BBC, it was an immediate success, receiving a ten-minute ovation.

The witch hunt is a perennial social dynamic, a kind of madness that never goes away, from political persecution to cancel culture. American playwright Arthur Millar’s 1953 play The Crucible famously used the 1692–93 Salem witch trials as a metaphor for the McCarthyism of his day. Closer to home, in 2001, historian Lynley hood used the witch trial metaphor to frame her book A City Possessed, about the Peter Ellis trial.

Aotearoa has its own history of dubious anti-witchcraft law in the Crimes Act, derived from the English 1735 Act, but rarely used except to prosecute the occasional dodgy medium or fortune teller, and repealed in 2013. Of far greater significance was Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907, which was partly passed out of concern regarding a proliferation of self-declared tohunga peddling dubious treatments, but also to use against the faith healers of Māori prophetic movements they regarded as seditious.

In the age of highly reactive social media, unsurprisingly it has become a virtual incubator of entitlement-fuelled twenty-first century witch hunts. It doesn’t take much, just as it only takes two locusts brushing wings to trigger a plague, and where once the engine of expression was transgression, it has been replaced by trauma of an increasingly performative nature. Here paranoia is rampant, and to use Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s distinctions, the focus is almost always that of bad faith attempts to find something wrong, rather than what is reparative, and pundits with platforms supercharge the discourse for clicks.

The Confession reaches out to these other forms of irrational mass panic, violence, and persecution as well. In the shadowy concrete walls of Silo6 the mind slips easily into thoughts of psychological, metaphysical, and physical confinement, but it is the audience who are the judge and jury here. Five artists present their work in all its vulnerability and courage. As curator Scott Lawrie says, the works encompass, “ideas of empathy, rejection, and abjection; equal parts Requiem…and reminder”. The infamous Scottish witch trials of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, rife with misogyny, resulted in the horrific torture and murder of hundreds of women, often strangled and burned. Scott has chosen five women artists and one male newcomer, to make up the exhibition part of the event.

The experience begins with a dramatic, purpose-built installation by Auckland-based artist Inga Fillary consisting of burnt furniture, modern, but resembling the sort of thing which might have been found in a medieval Scottish home. Ordinary modern tools are presented oxidised and aged, taking on the appearance of torture instruments. The counterpoint of old and new, feudalism and capitalism, summon up ideas of the way economic and social power can be brought to bare to control ordinary people beyond the direct allusions to Gowdie’s life and murder by burning.

UK-born Rebecca Wallis creates work that takes abstraction that references the experiential world of abjection with reference to Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection – both the bodily experience that unsettles the singular bodily integrity and with the messy realities of the mortal body that abstraction usually ignores. Wallis intuitively connects the bodily and painterly to both the transcendental and immanent. It is a deeply unconventional form of abstraction in its resistance to traditional artistic constraints and the serene, illusive allusiveness that slips outside of language. The act of painting becomes a metaphorical act of exploration, resistance, and liberation, blurring the distinction between introspection and outer reality.

There is an Old Master precision and naturalism to Rebecca Hazard’s oil paintings of raw meat that recalls the philosophical concerns, the ephemerality and brevity of existence, of Dutch still life painting. For her the meat is posing for a portrait as she explores the visceral aesthetic qualities usually ignored. The paintings invite us to consider the carnality of life, the inevitability of death, and our relationship, as ultimately meat ourselves, to nature.

Patricia Piccinini is easily one of Australia’s internationally familiar contemporary artists through her unique anthropomorphic silicone sculptures with their suggestions of dubious genetic engineering and unexpected consequences. While her creations would fit well among the lurid familiars of a witches’ sabbat or the victim of a malevolent curse, when we look past the Cronenberg-esque body horror we can see their vulnerability, humanity, and benevolence. Piccinini’s work is ultimately about empathy.

Monique Lacey’s sculptures are also an act of resistance. They take as their point of departure the cardboard box, bringing it into dialogue with contemporary existence and bodily experience in an aesthetic act of protest. Lacey crushes the box forms with the physical weight of her own body, alternately weakening or strengthening parts of them, and then decorating them with baroque extravagance. The viewer experiences the ebullient relics of the artist’s thought, action, and bodily presence.

The final component of the experience is a moving image work by emerging Auckland post-internet artist Amadeo Grosman. A Tall White Fountain Played takes its title from a line from a poem by the fictional poet John Francis Shade that lies at the heart of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire with its allusions to death and its ambiguous glimpses of the supernatural. Inspired by McMillan’s The Confessions of Isobel Gowdie, the viewer is bombarded by a relentless visual display which manifests another form of confession; that of a young artist utilising digital channels, social media, memes, and intimate recordings to disrupt any sense of a singular narrative.

Yet it’s not cut and paste randomness. Instead, the work is raw, compellingly voyeuristic, searingly honest, and at times frighteningly unanchored to the traditional comforting meta narratives that we are so used to experiencing in traditional art spaces.

The Confessions is a deeply moving spell of empathy that disrupts all of our preconceptions and biases and invites us into a reparative environment to reconsider our vulnerabilities and propensities for paranoia and crowd mentality.

It is a profound moment of humanity, both a requiem for the victims of persecution and a warning as a community against complacently joining in with the mob.

Patricia Piccinini / Amadeo Grosman

Patricia Piccinini / Amadeo Grosman

Inga Fillary

Inga Fillary

Rebecca Wallis

Rebecca Wallis

Rebecca Hazard

Rebecca Hazard

Amadeo Grosman

Amadeo Grosman

Patricia Piccinini

Patricia Piccinini

Monique Lacey

Monique Lacey

Introducing: Amadeo Grosman

A Tall White Fountain Played

FEATURED ARTISTS

Patricia Piccinini

Patricia Piccinini is one of the most popular – and controversial – artists in the world, having had over 55 solo shows in the past 13 years including Brazil (where over 1.2 million visitors came to see her show), USA, China, Malaysia, Germany, UK, Finland, Australia, Sweden, Denmark, Slovenia, Ireland, Lithuania and New Zealand. Patricia’s work can be confronting, engaging, touching and deeply emotive. Known for her imaginative, yet strangely familiar, ultra-lifelike chimera works (human/animal hybrids). With Prone a seminal work from 2011, Piccinini invites us to think about our place in a world where advances in biotechnology and digital technologies are challenging the boundaries of humanity, otherness, empathy – and perhaps even nature itself.

Inga Fillary

Inga’s installation for The Confessions has been purpose-built for this event. The furniture in this work, whist modern in design, was hand-picked for its resemblance to medieval Scottish furnishings, likewise the (harmless) modern tools have been aged and oxidised by the artist to appear as torture devices from the dark ages. This mix of old and new shines a light on the cyclic nature of human modes of social control; feudalism meets capitalism – two related economic models which exploit subordinate classes. Beyond the obvious connections to Gowdie’s life and death (by horrific burning), the artist attempts to wade into deeper concerns; a material challenge to capitalistic normativity both present and past.

Rebecca Wallis

Rebecca’s practice has predominantly utilised the traditional painting structure, while simultaneously questioning it. She makes analogies between the Self and the painting. Her methods characteristically involve simple and unconventional gestures, where she refers to herself as a conduit for the interaction between materials. In her work for The Confessions, Wallis exhibits a ‘slipping away’ and a resisting of containment, referring to the allusive felt experiences of the Self and it's fluid positions between Self and Other, Subject and Object. It is her understanding of being, outside of language, informed by Kristeva's theories of Abjection, Lacan's theories of the Real and Freud's theories of the Uncanny which are evident in this unique installation.

Rebecca Hazard

In painting choreographed mounds of meat, Rebecca Hazard's recent work speaks to analogies of the body as canvas, and paint as flesh. The confronting size and painstaking detail of Rebecca's 'grotesquely beautiful' oil paintings, are a humbling reminder of our own mortality and ephemerality, as ultimately meat and animal ourselves. Immersed in these recent, large works, two of which have been created for The Confessions, the viewer is made increasingly aware of the act of spectatorship as embodied within a complex system of flesh contemplating itself; conscious meat. Exuding its raw potential, we are reminded of meat's origins and our dissipating relationship to the natural world as part of the Anthropocene age.

Amadeo Grosman

Amadeo is currently in his final year of his Bachelor of Fine Arts at Massey University, Wellington. His unique, highly dynamic, and powerful 25-minute film, ‘A Tall White Fountain Played’ (2022) was produced as part of his degree for The Confessions project. Here, Amadeo has collected, collated, and collaged a high-octane, hi/lo-fi visual experience devoid of obvious allegory or metaphor. Instead, Amadeo is measuring his emotions with a warped mirror (gazed into by all digital natives) demonstrating a universal linguistic failing, an everyday alienation, which in turn drives his need to mediate that which he does or does not feel through the use of media. It is through this lens where he is able to experience pathos, connection, and creativity, all inextricably linked with the futility of our current cultural and economic condition and the desires it manufactures.

Monique Lacey

Monique Lacey’s ‘Nanny State’ (2022) explores recent social turbulence where women’s bodies – once again – are controlled by a patriarchal society shaped by evangelical hysteria and bible-blinded dogma. Flat-packed materials are realised into what could be a bodily form, yet while adhering to the truth of the material, we also know that such truth is malleable. The low hierarchy of the cardboard box or utilitarian paper bag is transformed and elevated, covered with plaster, paint, resin, rubber, wax, varnish and pigments. An act of crushing utilises bodyweight and motion, enacting a playful and aggressive execution that is sometimes cathartic or darkly humorous – body on bodily form. The original potential of the materials is rerouted, substantially reconfigured, much like the times we find ourselves living in now – at once resigned, melancholy, yet ultimately hopeful.

About The Gallery

Scott Lawrie Gallery aims to connect hearts and minds when it comes to encountering and experiencing contemporary art. Hearts for the naturally powerful 'love/hate/ignore' subjective response, and minds by exploring the cultural context within which the work was created. We believe that art has great power to connect human beings to each other, by creating new and meaningful insights into the extraordinary slice of time that we all occupy and share. We are proud to show a range of artists from around the world, with a focus on New Zealand, Australia, and the wider Moana Pacific region.

CONTACT: scott@scottlawrie.com

Scott Lawrie Gallery

Shed 10, The Steelworks

13 Coles Avenue, Mt Eden

Auckland, 1024 / New Zealand

All images © Samuel Hartnett / Scott Lawrie Gallery